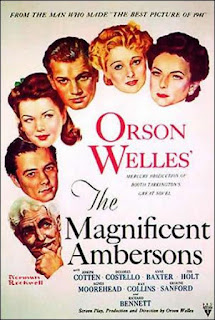

December 9th: THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS (Orson Welles, 1942)

The slow decline of a wealthy midwestern family contrasted with the rise of industrialization at the turn of the century.

After his triumphant but controversial debut Citizen Kane, all Hollywood eyes were on Orson Welles (still only 26 years old), wondering what he would do next. Surprising many, he opted to step back from Kane's sensationalism and adapt a novel from Midwestern writer Booth Tarkington, a Pulitzer Prize winner but one who had faded into relative obscurity since the 1910s. The project was also more personal for the nostalgic Welles, reflecting on his own childhood in Wisconsin and Illinois, his own father an inventor like one of the book's main characters.

Having already adapted the novel for a radio program, Welles was able to cast the film before writing the actual screenplay. He ditched an earlier draft by respected writer Ben Hecht (His Girl Friday) to create a new one, completed in roughly six months. Compared to his experimental Shakespeare adaptations, the script was particularly faithful to the source material.

Busy as he was, Welles opted not to appear in the film himself, instead opting for the important role of the story's narrator. The cast includes members from his Mercury Theatre group, some of whom appeared in Kane: Agnes Moorehead, Ray Collins, Joseph Cotten, and Erskine Sanford. Silent film veterans Dolores Costello and Richard Bennett are also featured alongside younger actors Tim Holt (John Ford's Stagecoach) and Anne Baxter (All About Eve). Welles spent weeks with the actors not simply rehearsing lines, but working on the character's backgrounds and relationships with each other. An attempt to record the audio of the rehearsals for the actors to lip-sync over on set proved unwieldy.

While less innovative than Kane in terms of camera tricks and editing, Welles did not shy away from pushing the envelope, most notable being the elaborate ballroom tracking shot relying on the complicated blocking of actors as well as the dexterity of the camera department, which took 9 days to shoot. Conversely, he also used long takes with little camera movement, urging his talented actors to improvise with their well-drawn characters. Outdoor location shooting was done at Big Bear Lake and San Bernardino National Forest.

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, even more talent from Hollywood was drawn into the war effort. Despite having a full plate, Welles agreed to work on a documentary film in Brazil at the request of Nelson Rockefeller in tandem with President Franklin Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor Police". Leaving the post-production duties to his associates, including Kane editor Robert Wise, he was out of the country when RKO Studios executives demanded cuts after negative audience remarks from a preview screening.

Despite having a print of his rough cut sent to Brazil, Welles had trouble negotiating and approving changes from abroad. His associates were forced to complete the cuts to the studio's demands, including shooting a new ending without Welles' consent. Approximately 45 minutes of the film were removed, primarily from the second half. Composer Bernard Hermann's music was mutilated to the point where he insisted on his name being removed from the credits.

Dumped into theaters with little fanfare, the film wound up as a financial loss, though critical reviews were positive. It received Academy Award nominations for Best Picture, cinematography, art direction, and Moorehead's performance. The excised footage was destroyed to make room in the RKO vaults, and earlier cuts are believed loss. Despite its mutilated form, it is regarded as an artistic triumph by Welles, and in Sight & Sound's magazine's once-a-decade poll of critics and directors it was twice voted one of the ten best films ever made, in 1972 and 1982.

Running time is approx. 90 minutes.

Comments

Post a Comment